These are some of the greatest historical finds unearthed in Sheffield as Netflix film The Dig gets everyone interested in archaeology

and live on Freeview channel 276

The Dig, starring Ralph Fiennes and Carey Mulligan, has just been released on Netflix and dramatises the discovery of an Anglo-Saxon burial ship in 1939 at Sutton Hoo in Suffolk.

Fiennes plays Basil Brown, a local self-taught excavator who is hired by Mulligan’s wealthy, widowed landowner Edith Pretty to investigate a series of raised mounds in her fields which, it transpires, contain an astonishing hoard of treasures.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGoogle searches about Sutton Hoo have more than doubled in the UK in the last seven days, while queries about the Portable Antiquities Scheme – a government programme that records small finds of archaeological interest made by members of the public – have shot up in the same time period.

While the Suffolk episode was truly exceptional and the stuff of any museum curator’s dreams, many remarkable finds have been dug up in and around Sheffield over the years.

The city’s biggest recent archaeological endeavour was the dig to excavate the remains of Sheffield’s lost castle, which yielded some landmark discoveries.

The two-month archaeological dig took place in summer 2018 on the vast space cleared when the city centre's indoor market closed and moved to The Moor in 2015.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMany finds, including medieval pottery, tiles and even an ancient 'ear scoop', were dug up from 11 deep trenches, while boreholes were created to take samples from the earth.

Experts believed they found evidence of around 1,000 years of constant activity, and the site's 'motte and bailey phase' – these were fortifications that stood on top of a raised earthwork, representing the first proper castles to be built in Britain.

Sheffield Castle, where Mary Queen of Scots was imprisoned for more than a decade, fell during the Civil War when it came under siege from 1,200 Parliamentary troops.

This stronghold was preceded by a late 12th century castle, which would have followed the 'motte and bailey'. These finds built on earlier excavations of the site; in particular, trenches were dug in the 1920s before Castle Market was developed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMeanwhile one of Sheffield’s most well-known Dark Age relics is the Benty Grange warrior helmet, which is held at Weston Park Museum.

The Anglo-Saxon helmet – the first ever found in England, pre-dating another unearthed at Sutton Hoo – was discovered in 1848 on farmland at Monyash in the Peak District.

It is made of seven iron bands which form the basic framework, and decorated with a boar on top and a cross on the nose guard. Museums Sheffield, which runs the Weston Park facility, says the helmet was made at a time when people's beliefs were changing from paganism to Christianity, a shift the item reflects – the boar was a Pagan symbol of fertility, strength and vigour and was often used as a protective symbol on helmets.

Academics think the helmet’s existence suggests the Sheffield region was a firm part of international trade networks as early as the eighth century, and that local metalworking was probably already making the area wealthy at that point.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

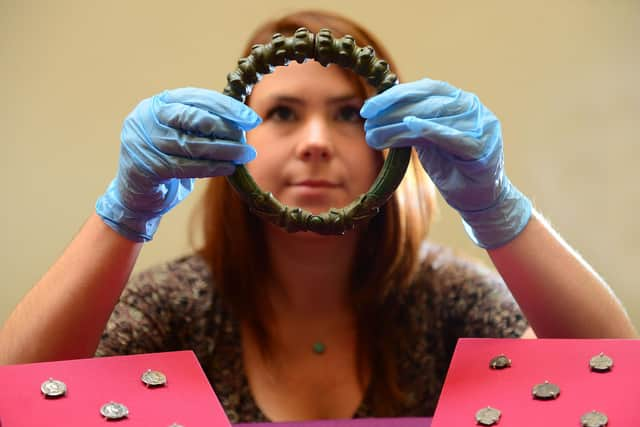

Hide AdImportantly, traces of Roman activity have been found in and around Sheffield too. Silver coins from the first and second centuries were chanced upon by workmen in Pitsmoor in 1906, and a copper neck decoration was excavated in Dinnington in 1984.

A cache of coins dating to the second century BC was also found in 2012 in a farmer’s field near Mosborough. Just like the Sutton Hoo discoveries, these coins were subject to a coroner’s inquest to decide whether the money should be declared treasure.

The five republican silver denarii were found at Plumbley by a metal detector enthusiast. The find was reported to the authorities before the inquest ruled the valuable currency was the property of the Crown.

The Star reported in 2013 that the finder would receive a cash reward, along with the landowner.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdArchaeology expert Amy Downes, who examined the Plumbley coins, said the oldest dated from 211BC to 120BC. She said the money was probably hidden or lost from a purse some time after 74AD.

“It’s quite unusual to find a group of such early silver Roman coins,” she said. “The hoard was probably personal rather than anything deliberately buried.”

Ms Downes said Roman republican coins were ‘known for their longevity’, and went out of circulation in the reign of Hadrian, 117AD to 138AD.

A soldier or unskilled worker living in the first century AD could expect to earn one denarius for a day’s work.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnyone tempted to take up amateur archaeology is encouraged to follow the Code of Practice for Responsible Metal Detecting in England and Wales, a voluntary set of rules endorsed by the likes of The British Museum, the National Farmers’ Union and the Portable Antiquities Scheme.

People are advised not to trespass – “Before you start detecting obtain permission to search from the landowner, regardless of the status, or perceived status, of the land,” the code says – and to obtain public liability insurance ‘to protect yourself and others from accidental damage’.

“Any finds discovered will normally be the property of the landowner, so to avoid disputes it is advisable to get permission and agreement in writing first regarding the ownership of any finds subsequently discovered,” the code adds.

It is illegal to use a metal detector on Scheduled Monuments without permission from Historic England, and similarly metal detecting is not permitted on some Sites of Special Scientific Interest without the permission of Natural England. If human remains are uncovered the police must be notified.