Sheffield Victorian 'Queen of Heeley' poisoned her lover

and live on Freeview channel 276

When the exhibition is the National Emergency Services Museum’s new offering, exploring the dastardly crimes of Victorian England and the daring detectives who solved them, digging up some salacious stories is almost guaranteed.

The story of Sheffield’s Kate Dover is not, however, the kind of tale that might immediately spring to mind when thinking of a Dickensian murder mystery. There are no ragged rogues, no pauper pickpockets and no dodgy dealings in the dark corners of a smoggy city.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis was a middle-class crime that became the talk of Sheffield and made national headlines too.

Kate was something of a local ‘sweetheart’ so it’s fitting that she ran a sweetshop on London Road. In 1880 she was 27 years old and, despite a humble background as the daughter of a woodcarver, was known to enjoy the finer things in life.

At a time when women were expected to be quiet and compliant, and to find a husband to support them, Kate bucked the trend by retaining an independent lifestyle. She attended the Sheffield School of Art and claimed to be vegetarian as well as teetotal.

She was highly intelligent, writing a book at the age of nine, and enjoyed standing out in extravagant and fashionable attire. It’s no wonder she earned the title the ‘Queen of Heeley’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPerhaps it was this individuality that attracted the attention of Thomas Skinner.

Thomas was an etcher, inventor and oil painter from Sheffield. His impressive career had seen him gain patents for his inventions in the UK and America and even saw his work mentioned in the 1851 Great Exhibition.

When he came home to Sheffield he was able to enjoy a comfortable life living off the funds from his inventions and other works.

By 1880 61-year-old Thomas was a widower, living at 24 Glover Place, Sheffield. Despite reports of heavy drinking and an ‘over-familiarity’ with his servants, he remained in high esteem in the city and in his profession.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was at this point that Thomas and Kate found their way to each other. According to letters written by Kate, they met when Thomas bought sweets from her shop and eventually they began courting. Soon Kate took on the role of housekeeper for Thomas, replacing Jane Jones.

Love letters between the two show that, despite the age difference, their relationship blossomed and they became engaged.

Some people disapproved of the match, including former housekeeper Jane who apparently tried to cause problems and was ‘never kind’ to Kate. These letters, later published in the press, suggested nothing but a loving and affectionate relationship.

This happy world came crashing down in December 1881. A doctor was called to Glover Street to find Thomas vomiting and writhing in pain and Kate feeling ill with a ‘burning sensation’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdKate recovered but it was too late for Thomas; at 9pm he was pronounced dead.

The post mortem revealed a sensational development - Thomas had been poisoned by arsenic.

Arsenic pervaded almost every aspect of life in Victorian Britain. Alongside numerous cases of accidental poisonings, morbid descriptions of murders with arsenic terrified the public and became a staple of the popular press.

The investigation found arsenic in the meal that Kate had prepared for her lover, in particular the stuffing.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAccording to court records the stuffing had been prepared and served separately and Thomas’ servant revealed that Kate had eaten only a very small portion, declaring that she felt ill.

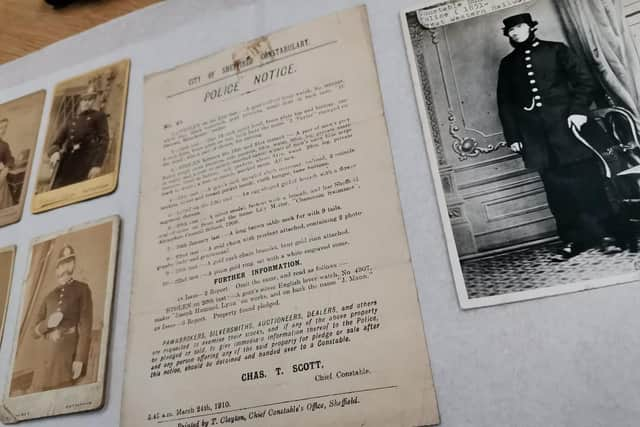

The police eventually concluded that Kate had indeed poisoned Thomas and she was charged with murder. It transpired that she had purchased arsenic from a chemist on Abbeydale Road, claiming she required it to colour artificial flowers.

On the day before the poisoning she had also been heard telling people that Thomas was ill and would probably die.

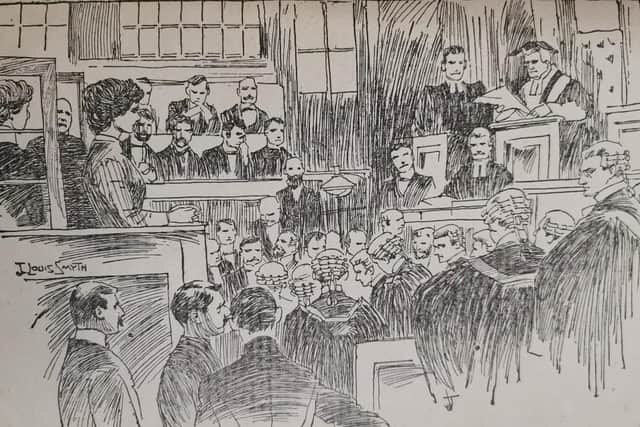

The story made headlines nationally and internationally and, when the case came to trial, Leeds Assizes was packed to the rafters.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne newspaper reported: "The case had created the greatest possible public interest, and the court was densely crowded, admission being obtained by ticket.

"Indeed, never since the trial of Charles Peace has the public excitement been so intense, hundreds of people being unable to obtain admission. Ladies mustered in unusually strong force.

"The prisoner, upon being placed in the dock, walked very slowly, and appeared to feel acutely her terrible position. She sobbed violently and pleaded not guilty in a feeble voice.”

After an intense trial and much deliberation Kate was found guilty of manslaughter. She had narrowly escaped the conviction of wilful murder as it was believed that, while she had indeed administered the poison, she had only intended to make Thomas unwell in order to accuse the former housekeeper, Jane Jones, and be rid of her at last.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhatever the truth, it is likely that Kate’s appearance in court as a fragile, grieving woman who made a tragic mistake helped to sway the jury.

A juror said they thought the reason they reached the verdict of manslaughter was because the majority did not want to hang a woman.

On February 8, 1882 a sobbing and quivering Kate was convicted and sentenced to penal servitude for life. She ‘fell into a heap’ and was carried away to the cells before being moved to Wakefield Prison and later Woking Female Prison, where she spent most of her sentence.

By 1901 she had been released, having served somewhere between 13 and 19 years, and was living with her sister in Rotherham. She never married and died of bronchitis and heart failure in 1925, aged 69.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo was this the story of a ruthless murderer or a young woman desperate to start married life without the malign influence of a jealous servant?

Whatever the truth, Sheffield’s Queen of Heeley had ultimately traded her glamorous lifestyle for the hard life of Victorian servitude.

The exhibition Daring Detectives and Dastardly Deeds: Fighting Crime in the 19th Century exhibition will open later in 2021.

In these confusing and worrying times, local journalism is more vital than ever. Thanks to everyone who helps us ask the questions that matter by taking out a digital subscription or buying a paper. We stand together. Nancy Fielder, editor