Sheffield retro: How bingo upstaged rock bands Small Faces and Saxon at city’s working men’s clubs

and live on Freeview channel 276

The path to the upper tiers of the rock 'n' roll world has always been peppered with pitfalls, yet it's arguable that facing the task of appeasing a "jumped up laborer with no interest in modern music" proved to be a gig too for many.

Why didn't they pick a different gig? Well things weren't quite as simple as that a few decades ago in Sheffield.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJust consider this: The Small Faces, the rock band Saxon, the sixties sensation Long John Baldrey, Worksop’s 'St. Elmo's Fire' author John Parr, and Sheffield luminary Dave Berry—all encountered the wrath of the club committee. These were the impeccably dressed, very old school decision-makers who presided over the UK's Working Men's Clubs, institutions that wielded immense influence during the late 1960s and 1970s.

Bands had generally managed to steer clear of them until changes in licensing laws saw the end of great swathes of 'teenage clubs'—venues like the King Mojo in Sheffield that didn't serve alcohol but attracted artists spanning Jimi Hendrix to The Who to perform for their audiences aged between 13 and 18 years old—in the late '60s.

Groups had no choice but to look to the Working Men’s Club circuit—a vast network of social clubs that were started by a teetotal minister in the Victorian era—for work and a possible springboard to fame.

The only problem, provided they were given a gig at all, was the fact that the star of the show was the game of bingo. In fact, everything revolved around bingo; the bands were essentially just killing time before the main event. It’s fair to say little could prepare artists for the kind of reception they got.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe first job was to persuade ‘the club committee’ they were worthy of gracing the stage.

Mark Rodgers remembers: “Acts quickly resigned themselves to routine humiliation. I remember we turned up to one club in Leeds late in full stage gear. The chairman looked at us in complete disdain and said, ‘If you think you’re coming into my club dressed like that, you can forget it.’ Being at the mercy of a jumped-up labourer with no interest in modern music became a regular occurrence.”

The Small Faces got their marching orders from a club in Sheffield after just two songs. Ronnie Lane remembers: “We’d come up from London to play in one of Sheffield’s clubs. After playing a couple of numbers, we were asked to leave.”

Getting your marching orders—or getting ‘paid up’ as it was known in the trade—halfway through a set became quite normal! Drummer Mike Hayes said, “John Parr band was paid up at Tinsley (in Sheffield) even though ‘St. Elmo's Fire’ was top of the charts.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut their were success stories from this unlikely of launchpads.

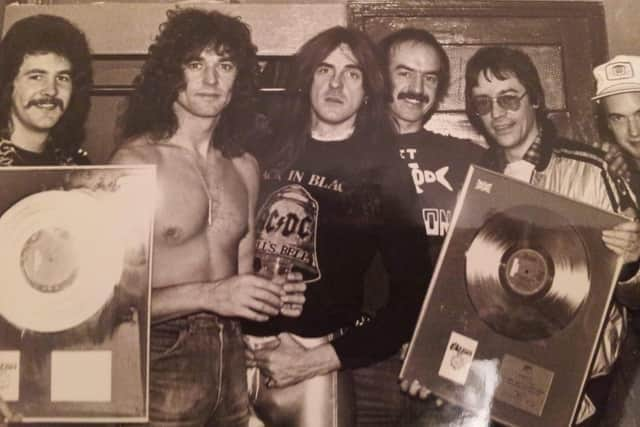

British rock band Saxon actually has clubland to thank for their big break—they signed their first-ever record contract at the Boilermakers Club in Sunderland in late 1978.

Sheffield drummer Pete Gill—who later joined Motorhead—said: “The back cover of the first Saxon album is taken in a Working Men’s Club. These venues had an unbelievable atmosphere. We’d arrive, and they’d be queuing around the block.”

But despite all that, something never changed. “We’d play two sets,” he added. “One on either side of the bingo.”

* You can read more about the British phenomenon in the 'Dirty Stop Out’s Guide to Working Men’s Clubs'.