I miss yer, Dad ... a first Father's Day without my boyhood hero

It was a comfort to those closest to him to see such a healthy turn-out, to know that he had touched so many decent folk in some way over the years.

But it wasn’t for him. Too much fuss, too much messing about. What’s going on? Daft b*ggers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDad needed only his family around him to be content. All his life, everything had begun and ended with his wife and kids.

This is my first Father’s Day without him. Tony Davis died, aged 77, late last month. The pain is raw and it’s too soon to say how I’ll eventually feel, but everyone I know who has lost a good father says things are never quite the same again.

We didn’t have a lot growing up, yet we had everything. “I might not have much money,” he’d tell us. “But while ever I’ve got you lot, I’m a millionaire.”

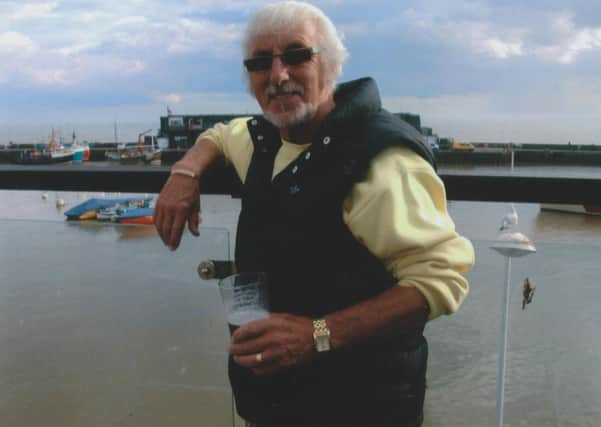

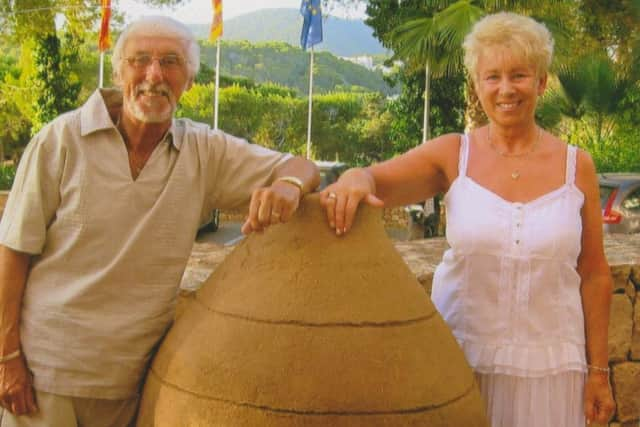

What he did have was time, and he gave it to his two sons and only daughter freely. We never went abroad, yet who needs the Costa Del Sol when you’ve got the East Coast, a caravan, amusements, beach footie and potted-meat sandwiches with sand in them?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDad had lost his own mum when he was 11 and had missed out on a lot of affection. It made him determined his own clan would never suffer like that. He was always loving, almost always looking for a laugh, often funny, regularly daft and now and again downright annoying.

My abiding memory of being young is him being strong and me feeling safe. He was a sales rep but should really have worked in a chemist’s because he had an affinity for nasal sprays, sticks and rubs like no other.

Many was the night I’d be lying in bed when he’d swoop unseen in the dark to baste my chest in some sort of olbas concoction or smear a pungent tincture under my nose. It was like the hands of God himself were upon me.

I’m not saying his nocturnal administering had a profound effect on me, but I did grow up to marry a woman called Vik.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEvery letter, every note, he ever wrote to family ended with ‘494’. That’s a Davis tradition stemming from the 19th-century hymn, God Be With You Till We Me Again, that featured in war-time hymnbooks. Soldiers picked up on the page number and said it to each other as they headed into battle.

Dad never owned a computer, never sent an e-mail and never went on the internet, although he did become quite daring in his later years with his texts. His mobile brick was far too old for emojis, but he perfected an ending to his messages consisting of entirely random upper and lower-case kisses and ‘capital D’ smiley faces.

Always, and I mean always, accompanied by those precious digits.

XxxXxX :-D :-D xxX x 494 x.

When my brother delivered papers as a teenager, he would be taken round in the car if it was raining. When my sister bought her first set of wheels, her windscreen would be de-iced for her before dawn.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

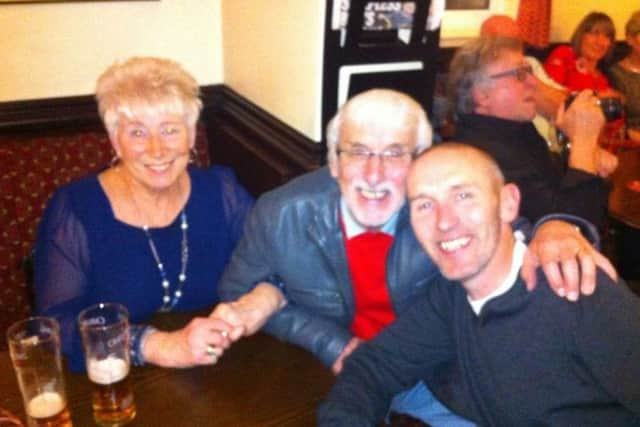

Hide AdWherever my mum was, he wasn’t far away. They were constantly together, joking, chatting, plotting, bickering, sometimes on the brink of a spat but neither seeking to be anywhere else. He was mad on her, she was mad at him. When he looked at her, no-one else existed.

He was fun-loving and open, she was a touch more proper, a little more reserved, although capable of the sweetest laughter when something tickled her. He told her daily he loved her and she’d pretend to be exasperated while revelling in it really. Only in Christmas and birthday cards would she say it back. Different people who completed each other.

He had several great loves: his children, his three grandkids, Rotherham United, Carling Black Label and, bizarrely, Little House on the Prairie. Every week one of us would walk into the lounge to find him watching one of the Ingalls girls in mortal danger and pretending, suddenly and more than a little suspiciously, that he had something in his eye.

There were only two great obsessions: my mum. And gravy. Every meal other than breakfast had to involve the brown stuff and, without a hint of shame, he would cadge little boats of it from snooty waiters in posh restaurants. Yorkshire born and bred, he liked things moist.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey loved their gardening and he kept a tin of bright-green paint in the garage which he would brush on to the tops of bushes to “help them along”. Nature, obviously, can’t make bushes green enough by itself. Once, he dug circles of such utter perfection in the front lawn that even the neighbours came out to marvel.

Mrs Davis was less impressed when she headed into the kitchen to find the best saucepan lids covered in grass and soil because they’d been used as templates.

I miss him. The minutes in a morning between waking up and getting up, when you’re at your most vulnerable and the day’s tasks have yet to draw their cloak of busyness against the grief, are the toughest. I talk to him. He doesn’t say much, but he’s a good listener.

He was my hero when I was a youngster, a man who guided me so well that I had no need for heroes as I moved into adulthood. I knew who I was and the difference between good and bad, right and wrong, gravy and dry. The biggest compliment I can pay him is that I tried to raise my own two sons with the values I first found in him.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith him gone, I cry when I least expect to. I was handed a toiletry bag containing his old medication to take away from the hospital. Nestled at the bottom were two little nasal sticks.

When the day was done, he and Mum would often drive a couple of miles to the Golden Ball in Whiston, Rotherham, the pub where they’d first met and he’d stolen her away from his best pal in the 1960s.

They rarely drank in the pub. They’d park up outside, he’d fetch the drinks and they’d happily sit in the car together listening to Football Heaven and putting the world to rights.

Their white Ford Focus with its distinctive DAD 494 X number plate - that was one hell of a Christmas present from my brother when all I’d bought was a crate of Carling - became known to everyone and they made a bunch of new friends as pub regulars stopped for a chat.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey even made an impression on people who weren’t using the pub at all. When the couple across the road had their first baby, they proudly carried it out to meet them.

“We were boring, Tony, weren’t we?” my mum said to him on his deathbed. “But we were boring together.” They were. They made the mundane magical.

His funeral took place at Whiston’s Manorial Barn on Wednesday. In view of the Golden Ball.

The end, when it came, was horribly tough. He had suffered a terrible fall a few days earlier, fracturing his skull, breaking his back, puncturing both lungs, fracturing his pelvis and breaking various other bones. It was testament to his physical strength that he managed to hang on at all.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI didn’t help matters by being undone by predictive text and conjuring up a rather unlikely image of hope for a concerned relative that he was “slowly skipping away”.

Dad had just hours left, drifting in and out of consciousness, heavily sedated, speech beyond him, when he reached for his wife’s hand and his swollen fingers took a tight grip that would be broken only in death.

My mum, drawing herself close, opened up like I’d never heard her before, speaking to him with exquisite grace and passion. She even told him how much she loved him.

His tired eyes were blurred and blackened but they opened and burned for her as 54 years of being soulmates came together in a final exchange made all the more eloquent by the silence on one side.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe’d found a way to say what he had to. When he looked at her, no-one else existed.

He faded from life as he’d lived it: holding on to his missus, embraced by his kids, surrounded by love.

494, Dad. XxxXxX :-D :-D xxX x 494 x.