Doncaster town that was built on water...

This town dates back to Anglo Saxon times but the peat extraction that until recent years still took place on the moors around the area also uncovered evidence of Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age settlers.

Thorne was part of the Danelaw lands that were taken over by Vikings but by the Norman Conquest in the 11th century, William de Warenne had become lord of the manor.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was the overlord who was responsible for the building of Conisbrough Castle.

According to the council website, Thorne’s isolation in medieval times, when much of the land was still underwater, served it well as it avoided the Black Death and famine.

One large expanse of water that separated Thorne and Hatfield caused the loss of a funeral party in 1326. The corpse and the bodies of 12 mourners were eventually recovered.

As a result, the church authorities agreed to the building of Thorne parish church so that the dead could be buried at Thorne, rather than Hatfield.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the 17th century, the arrival of Dutch drainage engineer Cornelius Vermuyden drastically changed the landscape.

Locals harassed the foreign workforce as they did not want the work to be completed. It created several serious floods but the value of the reclaimed land increased massively and it was turned to farming with the help of drainage dykes, waterways and sluices.

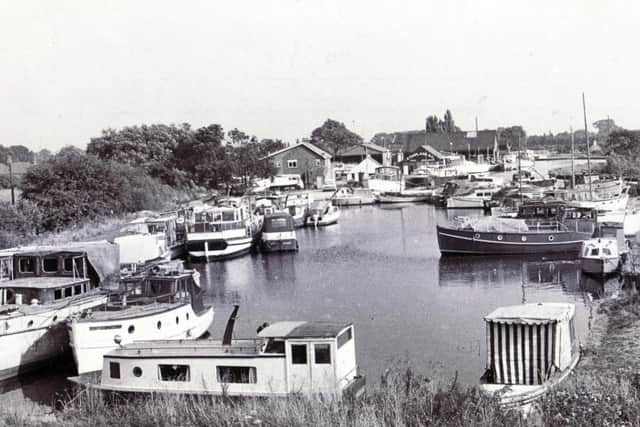

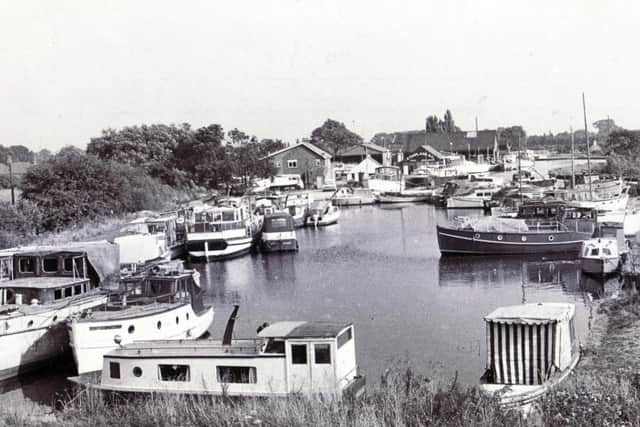

Waterways were still important sources of wealth, however, via the River Don. Thorne Quay or Waterside had its own shipyards, plus local warehouses serving international trade and inns, rope and sailmakers.

Trade grew even further with the construction of the canal in the 1790s.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBy the mid-19th century the railways began to take over from the river trade.

Thorne Colliery opened in the early 20th century, bringing workers and their families to the village from outside the area, so Moorends village was built to house them.

A dreadful accident in March 1926 claimed the lives of six men when the number two shaft was being sunk.

A platform that they were standing on gave way when an engine broke and the men were thrown 270 feet down into water at the bottom of the new shaft they were sinking.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThirty years later, floods and other problems led to the pit being put on to care and maintenance.

It was reopened in the early 1980s, when Thatcher’s government was already beginning to consider sounding the death knell of the coal industry.

Eventually, in August 2004, the colliery was closed and the pit heads were finally blown up.

Neighbouring Hatfield Main, which had been taken over by its workforce, closed last June, ending deep-mined coal in South Yorkshire.