Sheffield Victorian workhouse life - hard graft and meagre food

and live on Freeview channel 276

The admission records enable users to find out if their Sheffield ancestors fell on hard times, when they were admitted, their birth years and occupations.

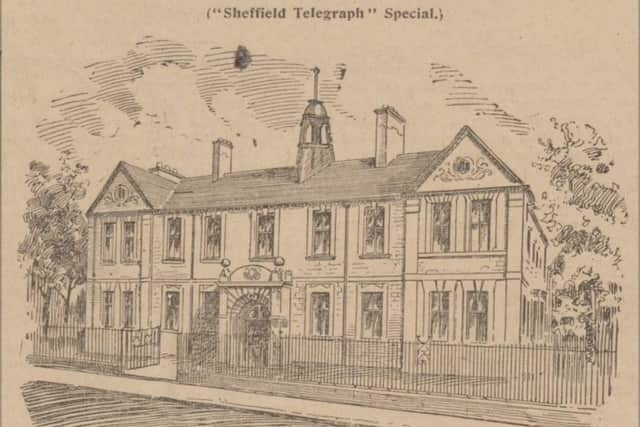

Researcher Alex Cox also found a highly detailed report on the Psalter Lane workhouse that was printed in the Sheffield Daily Telegraph in 1896. He said: “It provides an in-depth description of daily life and sheds light on the bleak conditions that inmates endured.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHere are some extracts from the letter, written by surgeon Rutherford John Pye Smith, following a visit.

The superintendent and his wife reside on the premises, which are separate from the rest of the workhouse, to admit casual paupers of either sex any evening.

On admission, each casual has to strip and bathe, and then has a dark woollen night dress given him and some rugs. He is then locked into small cell in which is a large plank that serves for his bed, with a raised boxlike end for a pillow. There is no other furniture; this plank is his table, chair, and bed.

A tiny inner cell opens out at the end, provided with iron grating of two-inch squares. In this inner cell the stone-breaking is done, and the broken stone has be thrown out through the grating. Each cell is provided with a bell, to call the superintendent in case of need.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTwo casuals only were the cells on the day of my visit, and they were both picking oakum (untwisting rope fibres). By Act of Parliament it is provided that every casual pauper shall perform a certain task in return for his night's lodging and board.

Men sleeping (as is usual) two nights in the casual ward are required to break from 5 to 13cwt of stone, or to pick 4lb of unbeaten oakum (or twice that quantity of beaten oakum), or to do nine hours' work digging, pumping, sawing or grinding.

Women are required to do half this amount of oakum picking, or else nine hours' work washing, scrubbing or needlework.

Of the two men present, one had got through about half his task in four hours. He had done such work before.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe other was a poor little fellow, one of whose legs had been amputated some months ago at the Fir Vale Workhouse. He was anxious to get in there again, the stump was sore from the pressure of his artificial leg, which had been purchased for him, he said, by a collection among kind friends.

He took the opportunity of our visit to ask leave for early discharge, in order that he might be in time to get an order for admission to the Fir Vale Workhouse Hospital that evening, and he was promised that his application should be reported.

Two pauper inmates were assisting in the casualty department. One had been there nine months, and was asked by my guide if he was allowed tobacco. He replied in the negative, but (doubtless emboldened by the query and, perhaps, also the fact that the guide was enjoying a cigarette) said had meant to ask if might not have a little. He too, was promised that the Master's consent should asked.

The number of casuals admitted through the year amounts to over 5,000, giving a weekly average of about 100, or over a dozen every day. The night-dresses and rugs are stoved once a week and washed "less often!"

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe dietary on which this work has to be done is as follows: At 6am, breakfast, 6oz of bread and a pint of gruel; at noon, dinner, 8oz of bread and 1 and a half oz cheese. At 6pm, supper, the same as breakfast.

It was a relief to turn from the prison-like casual cells to the recently-erected wood shed. Stone-breaking and oakum-picking seem unremunerative to all concerned but the sawing and chopping of old railway sleepers for firewood is a respectable trade, and in this shed a dozen or 20 men were busily engaged, under the eye of task-master, earning their own living, and thus helping to reduce the rates.

Some, indeed, were casuals, who would get nothing return for their work beyond two nights' lodging and the meals I have mentioned.

Some were inmates, glad thus occupied. Others were outworkers, technically paupers, but sleeping at their own homes, bringing their own meals with them and free to take home on Saturday evening their meagre and hard-earned wages.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPauper women working in the laundry get 2s a day for four days in the week, and their meals. It was now nearly noon and I was anxious to get the dinner served to the inmates, who number, all told, nearly 600.

It was meat-dinner day and I was allowed to see and taste the huge legs of boiled beef that were being rapidly cut up in to thick slices, weighed, and distributed to the company, who were ranged, as if for a lecture, along narrow tables facing the kitchen. It was certainly the coarsest meat I have ever come across.

Potatoes and liquor from the meat were served with it, and bread was supplied to each person. A large tin mug of water to drink out of, and a small bowl of salt, did common duty at each table.

The kitchens, bakehouses and pantry were then visited. The bread, admittedly unsatisfactory till a few months ago, is now considered very good. Black beetles are still a difficulty, but they are being much reduced by traps, and do not find their way into the bread and other victuals anything like so frequently as they used!

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPassing next through the dismal-looking chapel, we arrived in the quarters of the old married couples. The arrangement by which chronic infirm inmates have a separate apartment for husband and wife of more than 15 years. At present 10 such apartments are occupied.

I went to the next room, that couple nearly 70 years of age, who had been there many years. "Well," my guide asked them, "are you comfortable? Have you anything to complain of?" A short pause, and then the man replied: "That's a hard question to answer."

In these confusing and worrying times, local journalism is more vital than ever. Thanks to everyone who helps us ask the questions that matter by taking out a digital subscription or buying a paper. We stand together. Nancy Fielder, editor