The Leadmill Sheffield: Co-founder recalls how famous music venue was born and speaks out over ownership row

and live on Freeview channel 276

The arrival of a new landlord has focussed attention again on the city centre venue. What happens next on Leadmill Road is unclear.

The new landlord is The Electric Group, which grew out of the success of its refurbishment of the Brixton Fridge as Electric Brixton. It has served the current Leadmill management team notice and will take over running the club next year, saying it has plans to invest £1m and preserve the building as a music venue.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad

The current staff say they feel under threat and will strip the venue back to ‘a derelict flour mill’ if they are evicted. The club’s supporters have rallied to the cause. Scores of music stars and members of the public have thrown their support behind the #WeCantLoseLeadmill campaign because everyone seems to have a Leadmill story.

That is now and strife is no stranger to the site.

Just ask one of the original founders of the place, Chris Andrews, a self-confessed hippy in the 1970s when he and other dreamers had grand ambitions for a co-operative.

Who knew it would go on to be visited by Prince Charles and host world class talent long before anyone else had booked them? Think Madonna, Pulp and Culture Club. The place has a pedigree few can match.

Now aged 69, Chris was part of that. These days he lives in Thailand, two hours from Bangkok. But back in the day, he co-founded The Leadmill with John Redfearn, Adrian Vinken and Phil Mills.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdChris says John had the idea after a visit to Holland and the two discussed it as they moved from Reading to Sheffield.

“John had been to the Milky Way in Amsterdam which was The Leadmill as we set it up,” says Chris.

“The idea was first discussed in 1974 and two years later John drew up plans as to how it would look physically. He dreamt the whole thing up.”

Chris had studied at university in Reading and bumped into John in a commune.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We were into love and peace and lived in a commune called Let It Be," says Chris.

John moved to Sheffield and wanted Chris to do the same.

“John started looking for a place in Sheffield but I got involved in a project with mentally handicapped people in Edinburgh. John came up a few times to ask me to help him look for somewhere,” he says.

“By the end of 1979, he found the place and I went to see it. He showed me The Leadmill and said ‘This is where it can happen.”

Chris says the former flour mill was owned by Walter Fox and Sons, a motor parts company.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It had been empty for 20 years, was broken down and dilapidated. I had £500 which was my life savings and we were going to do this,” he explains.

This was the dream and they dreamed big.

“What we dreamt of was a community arts centre for the unemployed to bring the people of Sheffield together in a shared communal experience,” he says.

The place needed a front man and Adrian Vinken, who went on to run a theatre in Plymouth, was chosen. Things started developing.

“Don Fox, owner Walter’s son, gave us the building for free. I had burnt out in Edinburgh so I came to Sheffield and lived with John in the red light district of Broomhall. There were rats running across my sleeping bag,” he says.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We brought together a team of volunteers to form a non-profit making co-operative, which was registered as the Leadmill Co-operative.

“We got organised, talked to the fire brigade and the police. A community architect called Marcus O’Hagan was on our team.”

Hugely respected, Mr O’Hagan helped transform the place.

“We cleaned the place up and I went to the drug squad and said this is who I am,” says Chris.

Which meant telling them about a conviction for marijuana.

“When I asked if we could put our plan together, they said fantastic as long as there are no drugs,” says Chris.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“So Adrian applied for the licence and we ran one-off events to raise money. We had a temporary licence and people from the Youth Opportunity Scheme helping us with the carpentry. The concerts became more frequent and as they did the first thing we had to do was build toilets.

“The Esquire Club was on the top floor and buses were run between us and Stringfellows in London.”

They had allies and allies who could put their money where their mouth was.

“Don Fox was into what John Redfern said. You’ve got to remember this was the time when Margaret Thatcher was closing coal mines and factories, there were 900,000 unemployed in Sheffield,” says Chris.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Art and entertainment would be an alternative to the suicidal nightmare of living under Thatcher.”

It suited Sheffield, where David Blunkett was running what was referred to as the People’s Republic of South Yorkshire.

Chris says: “The early 80s in Sheffield were just an amazingly fun time for people with enthusiasm and ideas cos people like David Blunkett and Helen Jackson were there to support us.”

He adds that Rock On The Rates, organised by The Leadmill when he was events manager, got a £30,000 budget from the council. It was 1981.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“A lot of money 40 years ago to put on events and workshops for every disadvantaged and marginalised group in Sheffield along with all ethnic minorities,” he says.

“The Tories and the Tory press crucified us for wasting taxpayers money. About a month later every major city in England lost multiple millions in two or three nights of riots against Maggie Thatcher. How much did Sheffield lose? Zero - the best 30k investment of all time.”

By 1982-3, Chris says, the venue was running full-time and by the mid 1980s it was winning awards from the NME as the best club in the country.

But it was still a community arts venue.

“It was called the Leadmill Community Arts Centre. It was never called The Leadmill until much later,” says Chris.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We had a resident theatre company, a dance company, performing arts, and a whole spectrum of exhibitions.

“By 1986 it went from success to success. We were making enough money to pay the bills and support the on-going arts projects. The theatre company was touring and on a Tuesday night a visiting theatre company would visit us.

“We had rehearsal rooms, Pulp did their first gig on a Saturday afternoon, Culture Club played when they were number one with Do You Really Want To Hurt me.

“I had booked them for £200 and when they went to number one and I asked Boy George if they would still come.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“He asked how much we were charging the punters and I said a quid, 50p for the unemployed. He said ‘we’ll come’.”

By now, Chris was a producer at the BBC and says he felt he was being pushed out.

“I was made to feel unwelcome, they wanted me to resign as a director so I did,” he explains.

The co-operative had ceased to exist, the Leadmill Limited was born.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdChris says: “You couldn’t run a nightclub without having a proper company. It was to support the artistic side.”

But the parting of the ways was clear.

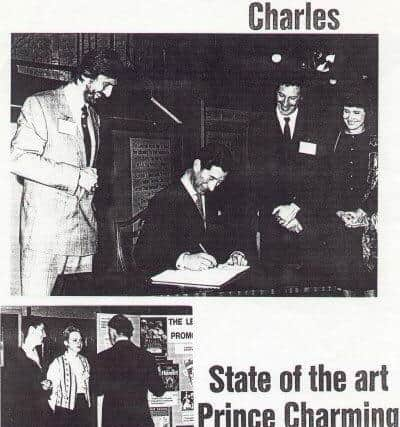

“When Prince Charles visited the Leadmill in 1988, I was asked to stay outside while Rony Robinson interviewed the prince inside for Radio Sheffield,” says Chris.

He moved to Thailand in 1988 where he is now based, running a company called BM Asia, provider of background music solutions to more than 400 hotels, spas and retail outlets throughout Asia. He is now married with a 13-year-old son.

Chris’s last visit to Sheffield was in 1999 and much has changed. So how does he see the venue now?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It has gone from a co-operative to a commercial concern. A community arts centre to a profit-making nightclub,” he says.

I suggest that was inevitable, as the venue was in a fiercely competitive market which has faced enormous challenge.

“That was not inevitable,” he responds. “All the money it made should have supported the community arts for the working class people of Sheffield.

“We always knew it could make money if you stop concerts for minority tastes and just focus on a DJ playing records.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe says the city council and now defunct South Yorkshire County Council all put money into the venue, which makes it a place for the people of the city.

“It is a great venue but another great venue was lost in making it,” he says. “It could have supported the theatre group, the dance groups and putting on events for minority interests across Sheffield.

“That’s what it was designed for and not so much profit-making. I don’t bear a grudge, it is a fantastic venue but it could have been so much better.”

It’s an interesting take, not one everybody will support as there’s no doubt The Leadmill continues to be a hugely popular venue, still booking acts which will later become superstars.

That is part of the founding vision. As for the co-operative, it all depends on your point of view. Your view of the Leadmill, a name to be reckoned with.