Football: Sheffield author's book tells how the national game played on during the First World War

and live on Freeview channel 276

His book Football’s Great War covers the story of the national game on the English home front, filling a gap in histories of football, wartime sport and civilian life.

Alexander says: “This is the first time this has been done as a totality. There have been specific studies or elements in club histories, but this is the first attempt to chronicle the home front story.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I was lead curator in 2014 for a First World War centenary exhibition where the role and history of football was covered.

“But there was a gap from the home front which seemed under researched so when the exhibition finished, I started to research and explore. It quite quickly became apparent that there was interesting material.

“The period is passed over. You have the Khaki cup final and the idea then is that football disappeared.”

He is referring to the 1915 FA Cup Final when a ‘sea of khaki’ was created by thousands of soldiers in the stands. Sheffield United beat Chelsea in what was the last final to be staged because of the war.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It is often thought the FA banned football,” says Alexander. “But what was done was banning payment of players. Some thought men shouldn’t be paid to play football during a war.”

Football and money, bedfellows then and even more so now. Imagine how the footballers felt as cricketers continued to be paid.

“It was a reaction to criticism at the start of the war where some were opposed to sport carrying on because it was inappropriate, not the right thing when men were fighting on the front line.

“There was a fear this was too commercial, that has always been a worry in the game.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSome clubs stopped playing, others continued, so it became a regional affair. Standards dropped and the game changed. More women’s teams were seen and the scorelines became remarkable.

“Because players were not being paid and teams were disrupted, team-building was affected,” says Alexander. “Managers had a challenge putting a side together and running it. There was an increase in goalscoring because the quality control was varied.”

Take Stoke 16 Blackburn 0. But football didn’t go away and Sheffield was at the forefront of innovation, as you would expect of the birthplace of football’s rules.

“The city has a big important place in the story. Charles Clegg, who was head of the FA, was from Sheffield and he helped introduce the ban on paying players,” says Alexander.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The sports editor of the Sheffield Telegraph was Alf Martin and he went on to become president of the National Union of Journalists, which provided money for the dependents of journalists killed or wounded in the war.

“Journalists wanted to help the war effort and he helped lead that.”

Sheffield was also the scene of a famous derby day punch-up as two players exchanged blows, were sent off, continued on the touchline, were split up again and tried to get at each other as they were ushered down the tunnel. It made the infamous Billy Bremner and Kevin Keegan punch-up from 1974 look like child’s play.

Then there was a pitch invasion in 1917 during the Owls v Bradford game as the crowd took exception to a Bradford player being sent off.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"A few sailors led the invasion but the Wednesday goalkeeper took the Bradford player away, pushing him down the tunnel and then blocking it,” says Alexander.

“It was a different world.”

There are parallels.

“The place football has in modern life is so much more pervasive because of the Premier League and TV,” says Alexander.

“But there is still a sense of how important football is because when it takes place fans still turn up even if it is not the same opposition.

“They turn up, rain or shine - tens of thousands of them and one of the biggest attendances was in Sheffield for the 1917 Boxing Day derby when 21,000 saw Wednesday win 3-1.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

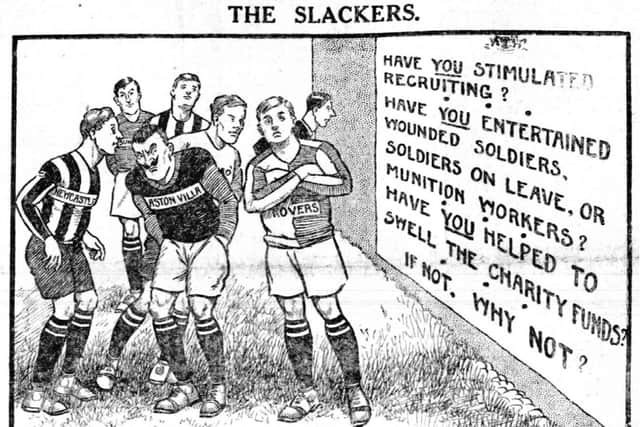

Hide AdThe pictures in the book tell their own stories. A cartoon called The Slackers shows the clubs which decided to carry on playing - which included the Owls and the Blades - telling those who stopped that they weren’t helping the cause.

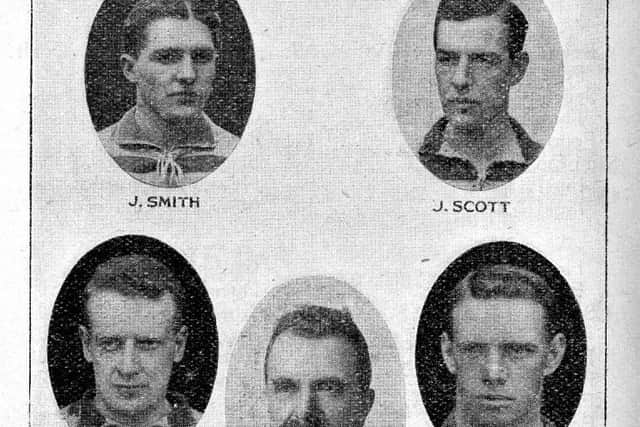

A picture of Hull City fans from the 1914/15 season shows how the crowd continued to turn up, including servicemen in training or on leave. Another of Park Lane Players from 1914-15 is included and shows manager Tom Maley, whose son was killed in action.

Two women’s teams from Portsmouth are shown in front of a sizable crowd, wearing hats.

“They were pioneering and played against men, who would have their arms tied behind their backs. The goalkeepers had one arm tied behind their back and had to kneel,” says Alexander.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Women’s football is important and got really big crowds, it goes back to the 19th century and there was an explosion of teams in the First World War including ones in Sheffield. A Boxing Day game between two women’s teams from the Vickers factory had a crowd of 10,000.”

Another picture shows the team from the Derby National Shell Factory. They wore striped tops and either skirts or aprons. The hats were worn to protect the women’s hair as they did in the factory to stop it getting caught in the machines.

“Women were looking for things to do in their recreation time away from the factory and football was a choice,” says Alexander.

Born in Sheffield, Alexander was raised in High Storrs. He went to school at Ecclesall Infants and Juniors before moving onto High Storrs secondary.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I was always interested in history and played football for the cubs and on Sundays. We used to get our results in the Green ’Un,” he says.

“The history interest came from my dad, who loved sporting history. There were lots of books in the house on it.

“As a child, I was taken to see castles and I really enjoyed history.”

He went to King’s College, London, to study history and supports Newcastle.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“My dad and his dad before him supported Newcastle, so it was a tradition. I was taken to St James in the days of the terraces, and the Gallowgate was something,” he says.

“Everyone at school was either Wednesday or United, but one thing they could agree on was not approving of children supporting other teams.

“Ironically, in the 90s I was accused of being a glory supporter.”

We’re talking Kevin Keegan as manager and Newcastle getting agonisingly close to the league title. The last time the Toon won that was 1926-7.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“All I could say was that the success was a long time ago,” says Alexander.

After university, Alexander did a masters in museum studies in Newcastle with the aim of working for a museum. He then did a collaborative PhD, where an academic institution teams up with a non-academic one.

The Football Museum, then based in Preston, was involved. Alexander started his studies there and finished in Leeds, studying football exhibitions.

He put on an exhibition about football and childhood. As the museum moved from Preston to Manchester, Alexander was offered a temporary contract to help make what was research become part of the galleries. He’s been at the museum ever since, working for 11 years as a curator, and, now aged 39, is back living in the High Storrs area.

Football’s Great War is published by Pen and Sword and the book costs £25.